Mary Anning: The Woman Who Changed Geology

By Sara Kurth

She sells seashells at the seashore. This popular tongue twister may very well be about little known fossilist, Mary Anning. Mary, born in 1799, was, for all intents and purposes, a nobody. But to geologists, and specifically, women geologists, she is a pioneer.

Mary was born in the town of Lyme Regis, England, which sits on the coast of Dorset and is the center of what is later to be dubbed the “Jurassic Coast.” The blue/gray cliffs of limestone and shale are some of the most unstable beaches in England, susceptible to the changing tides and frequent storms that inundate the area. The battle of sea and land provides ample opportunity for erosion – and ultimately the unveiling of fossils.

As a poor carpenter, Mary’s father hunted fossils for extra money. Around the age of 5 or 6, he began taking her out to hunt for fossils, an activity not common for girls during this era. He taught her all she needed to know about fossil collection and preparation. Her father unexpectedly died when Mary was 11 years old, leaving massive debts and forcing the entire family to work. Although she loved school, after the death of her father, Mary could no longer attend and often sought odd jobs. Unhappy with that prospect, she decided to return to the beach and search for fossils. On her first solo trip after her father’s passing, she found a “snakestone,” what later would be termed an ammonite. A well-to-do lady bought the ammonite from her, thus sparking her new “career” – seashell seller!

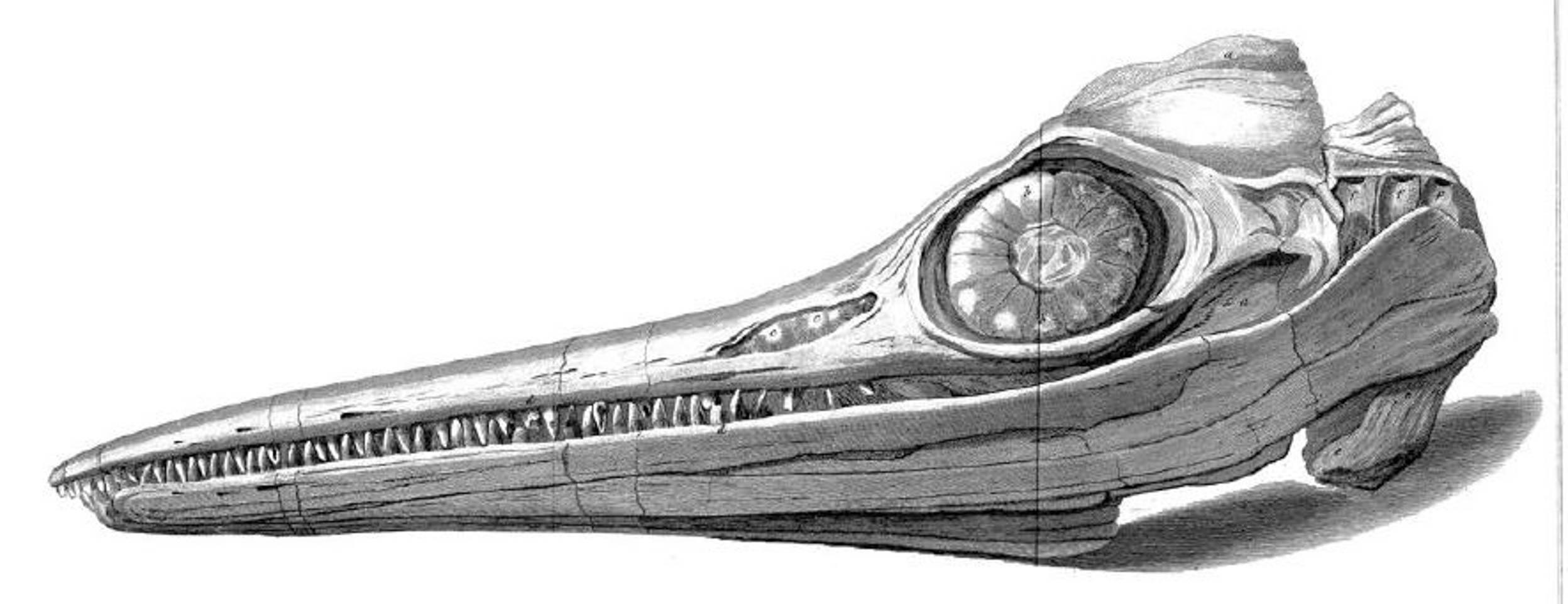

Occasionally her brother would join her on the beach. One fateful day in 1811, he discovered what he and Mary believed to be a crocodile’s head. It took Mary another year and many more storms, to find the rest of the body. Once fully unearthed, the complete skeleton measured 17-feet long with a 4-foot skull – the first complete skeleton of its kind ever found. This resulted in a slew of new questions for the scientific community as it was obviously not a crocodile. Eventually this new species was named – ichthyosaur or “fish lizard.” Mary continued to probe the cliffs of Lyme Regis and found many more ichthyosaurs, as well as another new species, the plesiosaur.

Her ability to find these fossils brought many scientists to the cliffs to search for fossils themselves, or more often, to utilize Mary’s keen ability to find and prepare the fossils. Unfortunately, women were not allowed to join the Geological Society of London and all her finds were sold to men who took credit for the finds instead. One scientist, William Buckland, was one of the few who gave Mary the credit she was due for her finds. But Mary would never be inducted into the Society or given credit for her work until well after her death.

Today, Mary Anning’s name is becoming more well-known. Her contribution to the field of paleontology is unprecedented. On March 5th the Museum is hosting a living history presentation featuring Mary Anning. A character interpretation will describe her life, along with other activities for children and adults to learn about fossils, as well as this remarkable woman’s achievements.

For more information about Mary Anning, check out these books:

Adult books:

- The Fossil Hunter: Dinosaurs, Evolution, and the Woman Whose Discoveries Changed the World by Shelley Emling.

- The Fossil Woman: A Life of Mary Anning by Tom Sharpe.

- Remarkable Creatures by Tracy Chevalier (a novel about Mary Anning and her friend Mary Philpot).

Kids books:

- Mary Anning’s Curiosity by Monica Kulling & Melissa Castrillon.

- Mary Anning and the Sea Dragon by Jeannine Atkins & Michael Dooling.

- Dinosaur Lady: The Daring Discoveries of Mary Anning, the First Paleontologist by Linda Skeers & Marta Alvarez Miguens.