Fall 2017

Interpreting Chinese Jade Pendants in the Lizzadro Collection: Part II Literature

By Ying Zhang

In the Lizzadro Spring 2017 Newsletter I interpreted jade pendants that were popular designs including auspicious symbolism and blessings. This article will focus on more unusual pendants that depict references to Chinese literature. These nephrite jade pendants feature the seal marks of the owner or maker and likely date from the late Ming and Qing Dynasties.

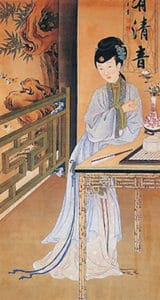

As one of many forms into which raw jade materials are crafted, jade pendants became popular during the Ming and Qing Dynasty (AD1368-1912), i.e., the Late Imperial Period in Chinese history. Jade pendants are designed to be used as personal accessories and are relatively small in terms of size, often made in square or rectangular shapes. Ancient Chinese people usually wear jade pendants using a string to hang from the waist. For example, we can take a look at the painting series from the Qing Imperial collection called “Twelve Beauties” commissioned during the reign of the Yongzheng Emperor (AD1678-1735). (雍正十二美人图) Pictured here is one of the paintings called “appreciating the butterflies in a summer leisure time” (消夏赏蝶 xiāo xià shǎng dié). The female figure is standing against a table, and we can observe a blue decoration from her waist.

The jade pendant the figure wears is a sophisticated china blue jade, knotted with the beautiful blue ribbon. On the table: Chinese chess, chess holder, paper fan, a vase with flower. The woman holds a calabash gourd: a symbol of flourishing growth. It is often used to suggest the idea of many sons.

There are two sides of the jade pendants that craftsmen would carve on: the front side presents scenes, patterns, or objects, while the back side is usually carved with poems or mottos. The contents of the front and back side echo mutually and deliver the same allegorical message. Because of its size and the auspicious meaning it carries, the jade pendant is very convenient to wear and ancient literati or aristocracy were fond of the small but exquisite pieces of jade. Let’s look at two good examples from the Lizzadro Collection that refer to Chinese literature.

This jade piece venerates the eternality of friendship. (一曲起|千古知音說至今) The sentence goes: with the tune, bosom friends of eternality communicate to this day. This literary quotation is concerned with a classic story of friendship during the Spring and Autumn period and the Warring States period (BC 770-221). It is said that the skilled Chinese zither master Bo Ya 伯牙 is playing his zither in the unfrequented mountain, but the uneducated woodman Zhong Ziqi 鐘子期 can surprisingly understand what Bo Ya is delivering in his tune. Therefore, they both realize that they can really understand and appreciate each other. After Zhong Ziqi dies, Bo Ya feels that he loses his bosom friend, so destroys his zither, and never plays again. The tune Lofty Mountain and Flowing Water 高山流水 is still one of ten ancient Chinese classical tunes.

The Chinese zither (guzheng) is a lap or table based stringed instrument. The zither is played by plucking strings and has movable bridges. The instrument has a long history and has been used in China for more than 2,500 years.

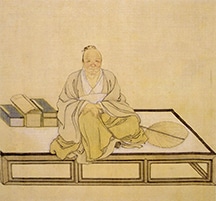

This pendant honors the Chinese painter and poet Ní Zàn 倪瓒 (1301-1374) who lived during the Yuan and early Ming periods. The poem on the back side writes: with his esteemed name literati Ni; the Spring wind breezes in the garden; his work Qing Bi Ge清閟閣; draw water to clean the tree called Wu Tong.

We can find one excerpt of Ní Zàn’s life story in a late Ming vernacular writer Feng Menglong’s “古今譚概Gu Jin Tan Gai”, which is characterized by a combination of stories of antecedent literati, jokes and satirical essays. In the original Chinese version, Feng writes that there are two boy attendants who help Ní Zàn with cleaning and drawing water under the Wutong tree.

The Wutong tree, species classified as Firmiana simplex, is commonly known as the Chinese parasol tree 梧桐; pinyin: wútóng. Wutong is a pun for “together” (tong 同). The Wutong is an ornamental plant of tree size that grows up to 52 feet tall and is native to Asia. It has alternate, deciduous leaves up to 12 inches across and small fragrant, greenish-white flowers borne in large inflorescences. The flowering tree varies in fragrance with weather and time of the day, having a lemony odor with citronella and chocolate tones. The Wutong tree is a key botanical image in Chinese literature related to desirable human character and symbol of personality. Wutong wood is used in musical instruments like the Chinese zither.

Ni Zan (倪瓚, 1301–1374), courtesy name Yuanzhen (元鎮) and pseudonym Yunlin (雲林), was a painter and poet of the Yuan Dynasty. He was a native of Wuxi (無錫) in the Lake Tai region.

Instead of serving the foreign Mongol dynasty of the Yuan, Ni Zan chose to live a life of retirement and cultivated the scholarly arts (poetry, painting and calligraphy). He collected artistic works of the past and associated with those of a similar temperament. Ni Zan was characterized by his contemporaries as particularly quiet and fastidious, qualities that are found in his paintings. Toward the end of his life, Ni Zan is said to have distributed all of his possessions among his friends and adopted the life of a Daoist recluse, wandering and painting in his mature style in the Lake Tai region near his hometown.

The art of Ni Zan and his peers in the Yuan dynasty was opposed to the preceding standards of the Southern Song academy, whose art immediately appealed to the eyes through obvious displays of virtuoso brushwork and a convincing pictorial reality. Ni Zan’s new style demanded concentrated viewing so that the larger and, in fact, more complex plays of ink could be perceived.

Generally it may be said that in his paintings, usually landscapes, he used elements sparingly, used ink monochrome only, and left great areas of the paper untouched, which suggests the expanse of water. There is often a rustic hut, without any further suggestion of human presence, a few trees and other scant indications of plant life, and elemental landforms with a somber quiet throughout. These sparse landscapes defy many traditional concepts of Chinese painting. Many of his works hardly represent the natural settings they were intended to depict. Ni Zan advocated that painting should be used to express personal emotions, rather than to depict physical resemblance. Ni Zan is regarded as one of the “Four Great Masters of the Yuan (元四家)”.

(China Online Museum 2017)

Ying Zhang received her Masters of Religious Studies specializing in Taoist philosophy at the University of Chicago in 2017. She studied several Chinese jade pieces in the Lizzadro Collection and presented programs.